These are the articles I read in the past four weeks that I found particularly interesting :). Some personal thoughts further down below :).

Energy

- World Energy Consumption Since 1820 in Charts

- Long-Term Clean Energy Optimism, Short-Term Caution Bloomberg New Energy Finance

- The Depression Of The 1930s Was An Energy Crisis Our Finite World

- New York City Plans To Divest $5Bn From Fossil Fuels And Sue Oil Companies

- ECB Admits Possible Role In Climate Change But Doesn’t Put Words Into Action

Geopolitics

- 2017 Zero Hedge Greatest Hits: The Most Popular Articles Of The Past Year And A Look Ahead [includes year end summary]

- US Intelligence Reportedly Gives Israel Green Light To Assassinate Iran’s Top General

- WSJ Is Seeking A Moscow Bureau Chief: Oath To Russiagate Required, Russian Language Skills Are Not

- “We Know Who They Are”: Putin Claims “State Provocateur” Behind “Terrorist Drones” In Syria

- Can The US Survive An EMP Attack?

- Scientists Discovered North Korean Defector Carried Anthrax Antibodies [For a further detour into the darkness of biological weapons see also Welcome To Vozrozhdeniya – The Deadly Germ-Warfare Island Abandoned By Russia]

Finance

- “This Has Only Happened Twice In History” – Goldman Asks “Should We Worry?” [Possible VIX Armageddon entering its final stage?]

- Deutsche: “We Are Almost At The Point Beyond Which There Will Be No More Bubbles”

- In Dramatic Reversal, China Gives Up On Deleveraging Pledge

- Petro-Yuan Looms – How China Will Shake Up The Oil Futures Market

- Treasurys Tumble, Futures Slide On Report China “To Slow Or Halt” Treasury Purchases

- Fed’S Dudley Is Worried About “Elevated Asset Prices”, Sees “Real Risk” Of Us Overheating, Hard Landing

- Fed Chair Powell’s Admission: “The Fed Has A Short Volatility Position”

- Here Comes The Debt Tsunami: Goldman Warns Treasury Issuance To More Than Double In 2019

- The Dollar’S Reign As The Global Reserve Currency Is Running Out – Fast

- The Rise And Fall Of The Eurodollar

- The Great Dollar Short-Squeeze Is Coming

- The Jim Grant Series: Former Governor Of The Bank Of England Mervyn King | Real Vision [behind a paywall]

Cryptocurrencies

- Riding The Blockchain Train: These Companies Changed Their Name, And Their Stock Price Soared

- A Stunning Look Inside The World Of South Korea’s “Bitcoin Zombies”

- Bitcoin “Wealth Effect” To Boost Japan’S Gdp Up To 0.3%

- Venezuela Is Recruiting ‘Miners’ For Its Cryptocurrency

- Ethereum Will Pass Bitcoin In 2018: My Cryptocurrency Investment Portfolio

Technology

- Deep Learning Achievements Over the Past Year

- Is Facebook Using Your Phone’s Camera And Microphone To Spy On You?

- Dystopian Vietnam Launches 10,000-Strong Cyber-Unit To Combat “Fake News”

- China Quietly Builds The World’s Largest DNA Database

- Intel Slides After Revealing Major Processor Flaw, Amd Surges

- “Everyone Is Affected”: Why The Implications Of The Intel “Bug” Are Staggering

Other

- Bridgewater’s Dalio Warns “There’s A War Going On… And Taxes Won’t Help”

- Un-Merry Christmas: The Perverse Incentives To Over-Consume And Over-Spend

- Alarming Link Between Fungicides And Bee Declines Revealed

- Drones Over Africa Target $70 Billion Illegal Poaching Industry

- Global Disasters Wreaked Havoc In 2017 – Total Economic Losses Top $300 Billion

- My 10 Favorite Books Of 2017 | Mark Manson [behind a paywall]

- Managing Procrastination, Predicting the Future, and Finding Happiness – Tim Urban [Podcast]

Ted Talks

- Christian Benimana: The Next Generation Of African Architects And Designers

- Angela Wang: How China Is Changing The Future Of Shopping

Photo Credits:

Further thoughts on my readings

On energy: In his Ted Talk about two years ago, Al Gore discussed his optimism on clean energy, in particular because of its now cheaper price with respect to fossil energy. The prices for wind and solar are now so low, that it’s become – more than ever – all about energy storage and grid redesign. To wit from Bloomberg New Energy Finance:

The question is no longer about how to promote wind and solar to enable them to grab a small share of each electricity market, but how to reform the rules of the power system so that as much super-cheap but variable renewable electricity as possible can be integrated into it.

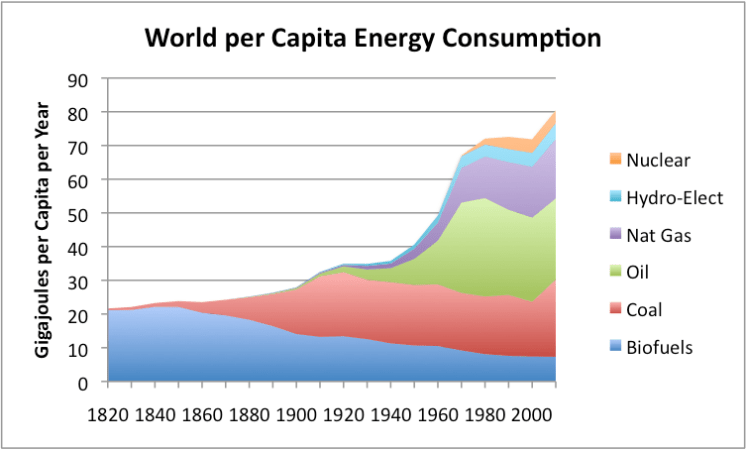

On the bigger picture – even as a statistician – it is still quite difficult to grasp the gargantuan amount of energy Homo Sapiens consumes each year. This is best illustrated in this per capita energy consumption chart:

However the chart is from 2012, so it needs an update, especially to encompass the now exponentially growing renewable sector. (As a reference, one return transatlantic flight requires about 20 gigajoules of energy, and the energy consumption per capital per year in Germany is about 160 gigajoules.)

Under the current status quo and a possible rise out of poverty of Africa, this chart will surely be interesting to monitor. The scenario described in the Ted Talk

Christian Benimana: The Next Generation Of African Architects And Designers

will require a lot of energy (especially on an absolute scale).

About: My 10 Favorite Books Of 2017 | Mark Manson [behind a paywall]

It always fascinates me how other people spend their time and especially what they read. With these two quotes in mind:

Reading, after a certain age, diverts the mind too much from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking.

– Albert Einstein

Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.

– Albert Einstein

I try to diversify my mostly article based reading more toward books. As such, the list of one of my favorite contemporary author – Mark Manson – comes in handy. I hope he won’t mind if I repost only his list as the whole article is behind a (cheap) paywall. (He will probably receive a remuneration if you end up clicking and buying one of the books referenced below on Amazon.)

- Fear of Intimacy by Robert Firestone (re-read)

- Rebirth by Kamal Ravikant

- Attention Merchants by Tim Wu

- The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

- The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Putin by Steven Myers [currently reading]

- Hillbilly Elegy by JD Vance

- Mastery of Love by Don Miguel Ruiz

- Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama

- Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents by Lindsay Gibson

- Emotional Blackmail by Susan Forward and Donna Frazier

- Too Good to Leave, Too Bad to Stay by Mira Kirshenbaum

- Out from the Shadows: Understanding Sexual Addiction by Patrick Carnes, PhD

- Seven Principles to Making a Marriage Work by John Gottman PhD

- Love Yourself Like Your Life Depends On It by Kamal Ravikant

- What I Wish I had Known Before I Got Married by Gary Chapman

- Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel [on my reading list, independently of MM’s recommendation]

- The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis [MM Top 10, not on my list but also one of my favorite authors]

- Originals by Adam Grant

- Toxic Parents by Susan Forward and Craig Buck

- Nabakov’s Favorite Word is Mauve by Ben Blatt

- Masks of Masculinity by Lewis Howes

- On Tyranny by Timothy Snyder

- The Course of Love by Alain de Botton

- When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

- Hit Makers by Derek Thompson

- Fundamentals of the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant [MM Top 10, on my reading list]

- But What If We’re Wrong? by Chuck Klosterman

- The War of Art by Steven Pressfield (re-read)

- Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics by Immanuel Kant

- Why Him, Why Her? by Helen Fisher

- Boundaries (re-read) by Henry Cloud and John Townsend (re-read)

- Perennial Seller by Ryan Holiday

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

- Explaining Unhappiness by Peter Spinogatti (re-read)

- Reasons and Persons by Derek Parfit

- A Feast for Crows (Game of Thrones Book 4) by George RR Martin

- The Retreat of Western Liberalism by Edward Luce [MM Top 10]

- The Last Wish (Witcher Series, Book 1) by Andrzej Sapkowski

- The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker (re-read) [MM Top 10]

- Sword of Destiny (Witcher Series, Book 2) by Andrzej Sapkowski

- Essentialism by Greg McKeown

- Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur

- Homo Deus by Yuval Noah Harari [MM Top 10, currently reading (independently of MM’s recommendation, his other book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind is currently my all time high favorite]

- Escape from Evil by Ernest Becker

- First We Make the Beast Beautiful by Sarah Wilson

- The Butterfly Effect by Jon Ronson

- Braving the Wilderness by Brene Brown

- The Thin Book of Trust by Charles Feltman

- Why Information Grows by Cesar Hidalgo [MM Top 10, potentially on my reading list]

- I Love You But Don’t Trust You by Mira Kirshenbaum

- Submission by Michel Houellebecq

- Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shinryu Suzuki

- Debt: The First 5,000 Years by David Graeber (re-read) [Maybe on my list]

- Dance of Dragons by George RR Martin

- Love Warrior by Glennon Doyle Melton

- The Infidel and the Professor by Dennis Rasmussen

- A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

- Still Writing by Dani Shapiro

- The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt [MM Top 10]

- Hourglass by Dani Shapiro

- Sum by David Eagleman [MM Top 10]

- The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression by Andrew Solomon

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert [MM Top 10, on my reading list]

- Godel, Escher and Bach by Douglas Hofstadter [MM Top 10]

- Impossible to Ignore by Carmen Simon

- Blood of Elves (Witcher Series, Book 3) by Andrzej Sapkowski

About The Jim Grant Series: Former Governor Of The Bank Of England Mervyn King | Real Vision [behind a paywall]

Synopsis: Former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King takes a seat with Jim Grant as the legendary financial writer brings the biggest names to Real Vision, with the candor to elicit the insights that you won’t see anywhere else. Mervyn King, Baron King of Lothbury, navigated the financial crisis during his decade at the helm of the UK central bank. Now he reflects on the absurdity of market models and widespread blindness as to what created the financial crisis, which impedes both the recovery and efforts to prevent another crisis in the future.

It is fascinating to have such a deep insight into the life of someone who used to be one of the most powerful men on earth… and you learn that his power is still quite limited in the grand scheme of things.

Some of my favorite insights from this very humble interview:

MK: So we’ve talked about how the financial system worked before the days of government intervention.

JG: Ah, then yes.

MK: Lender of last resort. And I think I came to the conclusion in the crisis that admirable though much of that might have been, we live in a world now where if there is a crisis, the government will step in as the insurer of last resort. If that is going to be the case, then it is very important that we diminish the moral hazard implied by that by making sure that the potential recipients pay an insurance premium before we get to that point in order to minimize the scale of the support that taxpayers have to provide.

[…]

JG: Quote, “Can’t you do something or say something to relieve people’s minds? They have made up their minds that something awful is up, and they are talking of the very highest names, the very highest.” This is beseeching the bank– governor of the Bank of England. And here is what the governor of the Bank of England thought to himself. If I– maybe this is the– yeah. If I do nothing, and the crash comes, I shall never be forgiven. If I act and disaster never occurs, Parliament would never forgive me for having pledged the National Credit to a private firm. So is that what happened in 2007? Those your night thoughts in 2007?

MK: Well, certainly all of those issues came to the fore. I don’t think we faced a situation in which an institution in 2007 as significant as Barings was in the late 19th century was at risk. We had the Northern Rock episode. And Northern Rock was a very good example of an institution that had done nothing out of the ordinary in terms of the nature of its operations. But the scale of what it did was such as to mean that its business model basically came to an end when the mortgage-backed security market closed.

And to my mind, one of the most disturbing things about the Northern Rock episode was that the new internationally agreed capital standards, Basel II, which had just been introduced at the beginning of 2007, made it possible for Northern Rock to say, we’re the best capitalized bank in the UK. And it true, according to those standards. And it’s quite difficult, if you have a regulatory regime where everyone is supposed to follow these standards, to blame a bank for saying, we’ve– according to these standards, which you’ve told us we should use– we are well capitalized.

In fact, their leverage ratio was outrageously high. It’s something like 80 to 1. So the standards were clearly wrong and absurd. And that to my mind suggests that it makes no sense to pretend that ex ante, looking forward, that any of us are going to be able easily to work out an appropriate international regulatory standard which will see us through a crisis.

JG: In the day, it was up to the individual bankers and the stockholders, who of course had mostly, for the 19th century, had personal responsibility for the outcome of– certainly for the debt of the firm.

MK: Yes. And we’ve removed that, do you see? By putting in place– as long as banks take risks, which are similar to those being taken by other banks– so they know they’ll all be in the same boat– then basically banks will say, well, look, if the whole system gets into trouble, they’ll be forced to cover that.

JG: Well, Mervyn, when the music is playing, you have to get up and dance.

MK: Well, that’s the argument. And I think these are issues we still haven’t really really thought through.

JG: They’re still front and center, no?

MK: Yeah. And what we’ve done instead is to put in place something that’s absurdly complex and detailed.

JG: And arrogant to the extent that somebody in Basel or elsewhere is deciding that a certain kind of security ought to get a certain weight of risk. They’re not bearing the cost. I mean, these people are intelligent, well- educated, well-trained. They mean well, except isn’t it yet again the nth demonstration of the futility of top-down direction of people acting in markets?

MK: And trying to pretend that there is a scientific basis for forecasting–

JG: The pretense of knowledge.

MK: Yes, it is. And you know, the belief that we can somehow decide what assets really are risky and which are not. And even today, I find if you go back, everyone is not only too ready to say, but it was obvious that these things were too risky, or that things were done that were crazy, because you’re blaming people at the time.

But we wouldn’t have made that mistake, is the presumption behind that comment. But that’s always shown to be false with history. The real danger here lies in those people who say, we can decide today what the risk weights are for different kinds of assets. And that will, therefore, prevent us from having another crisis in future. It won’t.

[…]

JG: But we have skipped over altogether a piece of early predictive machinery that is now, even today, I guess, situated in the boardroom of the Bank of England, which is a weather vane. Can you tell us– in conclusion, let us go back to things that work, Mervyn. Tell us about the weather vane.

MK: So this was installed in the 18th century, and it’s linked to–

JG: Can you describe it?

MK: Yeah, well, there’s a wind dial inside the courtroom of the bank, where the directors met, which shows the direction of the wind. And it’s linked to a weather vane on the roof of the Bank of England. So why did they want this? They wanted it because the direction of the wind determined when the ships could come up the Thames. If the wind was from the east, it would blow the sailing ships up the River Thames.

The cargo would be unloaded, and they needed then to ensure that there was sufficient money and credit to enable the merchants of the city of London to buy the cargoes from the ships. And when the weather– when the wind changed round to the west, from the westerly direction, the ships could then go back out again, and they could reduce the supply of money and credit. So the key indicator for determining the supply of money and credit was the direction of the wind.

Keep up the good work Gordon ! Love to read all the interesting articles you share

LikeLike